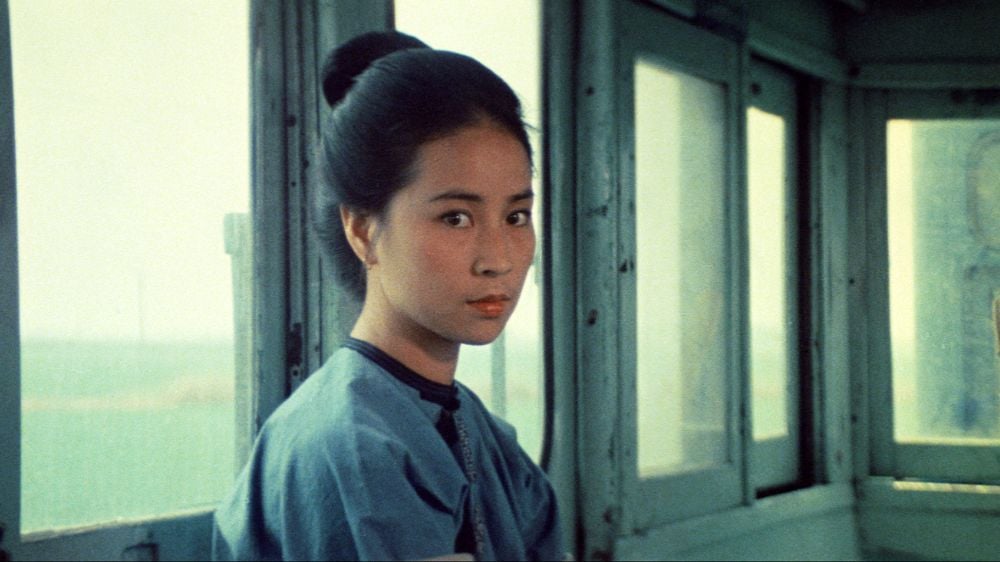

Chung Li-ho, a wealthy second-generation farmer, falls in love with one of his farm girls, Chung Ping-mei. While their differing social statuses don’t present an obstacle, marrying someone with the same last name is considered a taboo among the Hakka community. Two years later, Chung Li-ho returns to Taiwan and elopes with Ping-mei, hoping to seek a fresh start in his homeland of China. Li-ho drives a taxi to make a living, yet he can’t forsake his passion for writing. Ping-mei, despite her pregnancy, shoulders the financial load to support his aspiration. However, the pervasive anti-Japanese sentiments during the war eventually compel their return to Taiwan. Settling in the mountains, Li-ho works as a writer and teacher, but develops pulmonary disease due to years of hard work. Thanks to Ping-mei’s unwavering support and care, Li-ho finds the strength to face every rejection. He stays up many nights to transcribe his dreams onto paper, infusing every word with life’s spirit.

In the 1970s, Taiwan faced diplomatic setbacks, including its withdrawal from the United Nations. The one-party state government saw little prospect of countering Communism and restoring the nation, and in an effort to maintain social stability, it underwent a substantial shift in its propaganda-driven filmmaking approach, utilizing pop music to convey a new patriotic narrative – “the Republic of China is in Taiwan”. LEE Hsing, a pioneer in healthy realism and Chiung Yao’s “three-hall movies” trend, was acutely aware of this propaganda shift. The film’s choice to have Teresa Teng perform its theme song was a deliberate move to connect with the public, while Chung Li-ho’s yearning to return to his homeland aligns with the narrative of “connection to China”. On the surface, the film pays tribute to local writers, but its underlying propaganda intentions underscore the inseparable relationship between politics and art.